MISHA DAVYDOV

Misha Davydov (b. 1998, Moscow, Russia) works in photography and installation to investigate the tensions between object and representation, the material aspects of the photographic medium, as well as the constructed nature of reality. Davydov's works have been exhibited in a number of venues in Portland, Oregon, including Blue Sky Gallery, Well Well Projects, and Converge45. This summer, they have solo shows at Space Place Gallery in Nizhny Tagil, Russia; and at after / time collective gallery in Portland, Oregon. Their photographs have also been featured in publications by Booooooom and fifth wheel press. They hold a Bachelor of Arts in Studio Art from Lewis & Clark College and are currently attending UC Irvine, where they are pursuing a Master of Fine Arts.

Grey State (GS): As an emerging artist, have you faced any struggles or barriers in your practice? Were any of them due to your background?

Misha Davydov (MD): After graduating college, I went through a quite rapid process of getting to know a lot of people in the Portland art scene, getting jobs at two art galleries in the city, getting my first solo shows, and applying to graduate schools. It made me observe a lot of the invisible barriers and “rules” that the art world has, and realize the expectation that whoever wants to enter this world is just by default expected to know how to play the game. Navigating the art world as a non-US citizen specifically has been a big challenge. I was really lucky to meet incredibly generous people who I got to learn from or work with. A sense of lineage is very important to me, and I am eager to give back by helping as much as I can to those who need it.

GS: What does home and/or belonging mean to you? What does “community” entail?

Considering the war in Ukraine, I find it especially important to not get detached from the realities of Eastern Europe and realize the responsibility I have as a Russian citizen to fight against the imperial ambitions and colonial policies of the Russian state. The recent events gave me another push to stay in touch with my culture and the consequences of the actions of my government and fellow citizens. A part of the proceeds from my solo show at Grey State went towards the humanitarian organizations.

GS: Do you consider your art political?

MD: I don’t think my art is explicitly political, though I am still trying to navigate politics within my practice. I believe politics is everywhere around us, and it’s virtually impossible to deprive something of a political meaning. To me, good art raises questions rather than answers them. I think good art should challenge one’s view of the world. Questioning opens up new possibilities, which I see as an inherently political act.

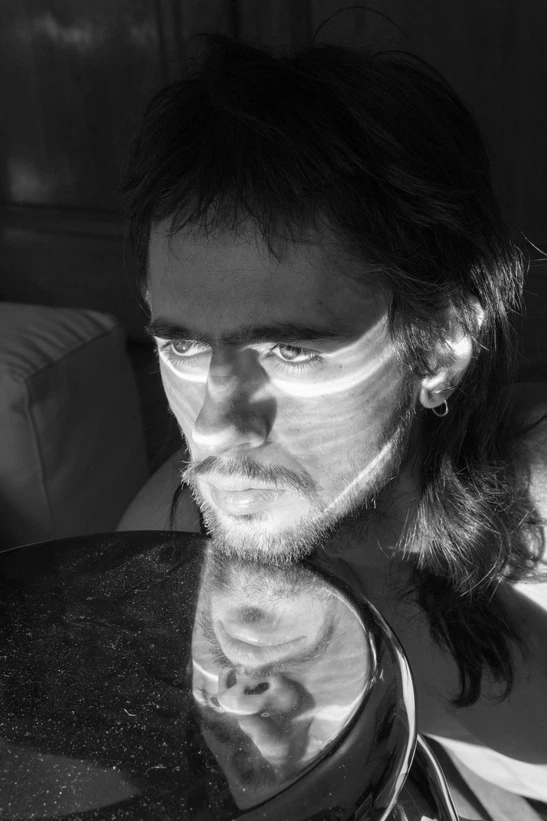

GS: How do you see yourself in your works?

MD: I consider all of my works—anything I make, really—to be autobiographical in one or another way. And I tend to treat all of my pieces as self-portraits, though sometimes covert. Primarily, it is the process of making that is personal. Oftentimes, I start a new piece because I am compelled to process something, resolve a tension within myself, and it is the process that allows me to feel differently. Performance is a part of my background, and I incorporate it into my image-making quite often. Physically negating the incongruities between the real and the fake lets me get closer to authentic experience.

It took me a long time to find a middle ground between highly personal narratives and abstraction. Early in my undergrad, I was making work that was openly referring to my family or specific issues within the cultural and political context in which I grew up. After a while, I became concerned that I am using the trauma that I possibly share with others, such as my family, in order to make my art. I thought a lot about the fact that those who were involved in the stories I considered had no agency or any voice within my pieces, which led to me having some moral dissonances with what I was making. It took me multiple years to find a solution and I think that my current mode of making helps me process the feelings or memories that serve as a starting point for a piece; at the same time the final result is often somewhat abstract. The difficult part is to find the right degree of abstraction. I strive to not disclose my point of reference for a piece too literally and want to give the audience an entry into a piece. I hope to spark some memory or evoke a sense that my viewer would want to spend time with, using a piece as a space onto which to project their interpretations.

GS: What do you, as an artist and an individual, represent?

MD: One of the disturbing tendencies that I have experienced in the art world is its tokenism. I reject the expectation that just because I am queer I should make work strictly about queerness, or just because I am an immigrant, all of my work is supposed to be about that. This pressure from the art market is another reason why I make conscious choices to push my work into a more abstract territory. Of course, my identity is embedded in my work but I don’t want it to create a fixed lens for the viewer to look at my pieces. I am always so glad to see initiatives with a genuine care for representation. I wish there were more spaces like Grey State that would give opportunities and resources to those who need them without trying to exploit artists’ identities.

GS: What is one thing that people can do to support art and artists?

MD: It might sound banal, but my biggest wish is that people recognize the amount of work, both physical and mental, that goes into making art. The reason why I chose to be an artist is because I felt like I could bring absolutely anything from my life into my practice and have making as a tool to navigate my lived experience. While it has been extremely rewarding, I also found it difficult to separate the job-aspects of my practice, if that makes sense, from the rest of my life. Some people are surprised by the price of a photographic print, for example, as if the only thing it takes to make one is to press the shutter button and then hit “print” on your computer. There is a lot of invisible work that artists do, and I wish it was more appreciated.

GS: What does “grey state” mean to you?

MD: The first thing I think about when looking at the name of the gallery is, foremost, ambiguity. There is a lot of power in the grayness. It allows for multiple interpretations, it gives freedom to see and to really reflect onto something, to activate the process of figuring out its true condition, true self, true state. In my practice, I utilize ambiguity in order to gain control over reality: my surroundings and the way I interpret them. Realizing that those things aren’t predetermined or fixed gives room to define them myself. A lot of the photographs I take are intentionally open-ended, don’t quite make sense, and keep the viewer wondering what is going on. I believe that a photograph of something observed is not any more real than a constructed picture. A gray state appears when I make decisions about what gets captured and what gets left out, what leaves a trace and what disappears, and what comes into existence despite its lack of sense, maybe.